- Admonishes public not to stigmatise ex-convicts

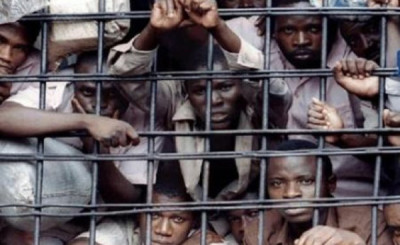

The Oluwo of Iwoland, Oba Abdulrasheed Adewale Akanbi, Ilufemiloye Telu I, on Thursday offered to pay the fines of five inmates of the Nigerian Prisons Service in Ilesa, Osun State.

Our correspondence gathered that the inmates have continued to be in prison custody for failure to pay an option of fines imposed on them by the courts.

Oba Akanbi made the offer during his visit to the prison in Ilesa, where there are 582 inmates out of which 454 are awaiting trial.

The traditional ruler, who made a donation of cow and cash to the prison service for the upkeep of the inmates, passionately appealed to the state Chief Judge, Justice Oyebola Adepele-Ojo, to look into the cases of those awaiting trial, many of whom had spent between two to twenty years behind bars.

Disclosing that his mission was to have first hand experience of the situation behind the wall of prisons and see areas he could intervene, the Oluwo said he was identifying with the inmates to give them hope and reasons to believe their lives could still serve good purposes.

The monarch also admonished members of the society to stop stigmatising ex-convicts and to make sure they are supported during their reformation, reintegration programmes for the society to be a good place for everyone.

While exchanging handshakes with some of the inmates, Oba Akanbi enjoined them to change from their bad ways and make sure they contribute to the peace and development of the nation.

He also appealed to the government to improve the facilities in the prison that have been built since 1900, adding that the prison environment, looking ancient, needed “serious rehabilation.”

Responding, some of the inmates said they were surprised by the monarch’s visit which they described as unprecedented, therefore promising to be of good behaviour during and after their jail terms.

They pleaded with the state government to grant those with good conduct state pardon while commending the officials of the prison for doing their best to better the lot of the inmates.

Also, the officer in charge of the Prison, who is a Deputy Comptroller, Mr. Ope Fanmikun, disclosed that his men face huge challenges, conveying 454 inmates for trial daily in 72 courts across the state.

“We take the inmates to court with just four vehicles. The newest of these vehicles was given to the prison four years ago. Presenting the inmates for trial has been difficult so we are calling on well meaning Nigerians to come to our aid,” he lamented.

According to him, the prison needs at least 20 vehicles, medical facilities and consumables, adding that some of the inmates that were supposed to be referred for further treatment in more advanced facilities could not do so because of unavailability of funds.